*Under a few conditions. But I have proof, trust me.

I was interviewing for a Software Engineering Intern position at a decent-sized company in Vietnam. Having passed the in-person interview with flying colors, I was ready to tackle the final take-home assignment.

And surprisingly enough, it was to implement a Big Integer expression calculator that:

- Supports additions, subtractions, multiplications and parentheses;

- Supports modulo (bonus feature, so I skipped that);

- Minimizes memory footprint.

The simplest implementation for Competitive Programming (in most cases) is from kc97ble. However, it doesn't deal with negative numbers. Another powerful and versatile snippet I have used in the past is from I_love_Hoang_Yen, which ended up being the inspiration for my implementation.

In this blog, I will be writing about Big Integer itself. For more details on expression parsing, please see the README of the repository.

Here is the repository of my code.

Algorithm

The algorithm is in fact the easiest part. If you have ever gone through elementary school, you should already know how to add, subtract, and multiply two numbers digit-by-digit. Yes, that's our algorithm.

Since our number is so big, we obviously cannot store them in an int or long long. We will read our input as strings first, then convert the strings into BigInts later.

To prepare for our algorithm, you may want to store all digits into an array for convenience. For now, I am using std::vector as array (but will replace it with something else later).

std::vector<int> get_digits(std::string_view number) {

std::vector<int> buffer(number.size());

for (std::size_t i = 0; i < number.size(); ++i) {

buffer[i] = number[number.size() - i - 1] - '0';

}

return buffer;

}

const auto a = get_digits("69420"); // {0, 2, 4, 9, 6}

The digits are actually reversed, but that's OK. That's my intention. It will make calculation easier and more efficient:

auto a = get_digits("69420"); // {0, 2, 4, 9, 6}

auto b = get_digits("1269420"); // {0, 2, 4, 9, 6, 2, 1}

// now b has more digits than a

// for example, to add each digit one by one,

// let's make both of them have the same

for (std::size_t i = 0; i < (b.size() - a.size()); ++i) {

a.push_back(0);

}

// a = {0, 2, 4, 9, 6, 0, 0}

// b = {0, 2, 4, 9, 6, 2, 1}

// same length

Because we are using std::vector, pushing to the back is much faster than pushing to the front. Other data structures will have some trade-offs that aren't worth it.

Adding (without carry) will be a simple:

std::vector<int> result(b.size());

for (std::size_t i = 0; i < b.size(); i++) {

result[i] = a[i] + b[i];

}

Support for carrying should be trivial. You can come up with a solution or read my code.

Internal storage

This is where things get a bit more interesting.

Digits

In the algorithm, we do calculation in base 10, which means a calculation involves two one-digit numbers at a time. That's pretty wasteful - computers can do more than that. We can do calculation in base 10^9. This means that for each calculation, we are calculating two nine-digit numbers at a time.

In the original get_digits, we only extract one digit at a time. Let's do 9.

std::vector<int> get_digits(std::string_view number) {

std::vector<int> result;

// reserve int(ceil(number.size() / 9))

result.reserve((number.size() + 9 - 1) / 9);

auto convert_range_to_num = [&](std::size_t head, std::size_t tail) {

long long num = 0;

for (auto i = head; i < tail; ++i) {

num = 10 * num + (number[i] - '0');

}

return num;

};

auto tail = number.size();

for (; tail >= 9; tail -= 9) {

const auto head = tail - 9;

result.push_back(convert_range_to_num(head, tail));

}

if (tail != 0) {

result.push_back(convert_range_to_num(0, tail));

}

return result;

}

If you can't understand the code right now, it's fine. Basically, here's its usage:

const auto a = get_digits("834752895720389374092984457");

// a = {92984457, 720389374, 834752895}

From right to left, it collects every 9 characters and makes that a number.

Why 9 characters? 10^9 fits an int and (10^9) * (10^9) fits a long long. We can't use more than 9 characters due to the risk of overflowing/underflowing. We can use less, but it's neither safer nor faster. This is why 10^9 and 10^18 can often be seen in Competitive Programming and/or interview problems.

basic_string and Small String Optimization (SSO)

This is another trick up in my sleeves.

So far, I have been using std::vector. However, std::strings (or std::basic_strings to be precise) are implemented a bit differently.

A dynamic array usually contains a pointer to the allocated data, a size and a capacity:

// Total: 24 (bytes)

struct Vector {

long long* data; // 8 bytes

std::size_t capacity; // 8 bytes

std::size_t size; // 8 bytes

};

Let's say, my Vector only has 1 element:

// Total: 32 bytes

long long* ptr = new long long[1]; // 8 bytes

auto vec = Vector { ptr, 1, 1 }; // 24 bytes

32 bytes to store 1 long long. That is also wasteful, and people have found a way to optimize it: Small String Optimization.

// Total: 24 bytes

struct Vector {

// Total: 24 bytes

struct Large {

int* data; // 8 bytes

std::size_t capacity; // 8 bytes

std::size_t size; // 8 bytes

};

// Total: 24 bytes

struct Small {

long long buf[sizeof(Large) / sizeof(long long) - 1];

std::size_t size;

}

union {

Large large;

Small small;

};

}

The trick lies in union. When the array is small, we use the memory that should have been for data and capacity for the array itself. We don't waste extra memory, and we don't create any dynamic allocation. SSO saves memory and saves time.

In practice, most of the numbers we deal with are small. And because they are small, SSO really offers a great performance boost. SSO is implemented in std::basic_string by major compilers (GCC, Clang, MSVC). What's even better is that you can use it in-place of std::vector.

Other implementation details

long long

Each "digit" stores 9 characters at a time. int technically should be enough, but overflows do happen during calculation. That's why I chose long long as the element type for the internal storage.

constexpr

I also wanted to try making my BigInt class constexpr-friendly. Well yes it is, but for now, being constexpr-friendly doesn't mean being constexpr (you can only use it as an intermediate value for calculation, not as the actual returning value). I read somewhere that the C++ committee rejected the idea of turning heap allocation constexpr.

Actual result

Addition & Subtraction

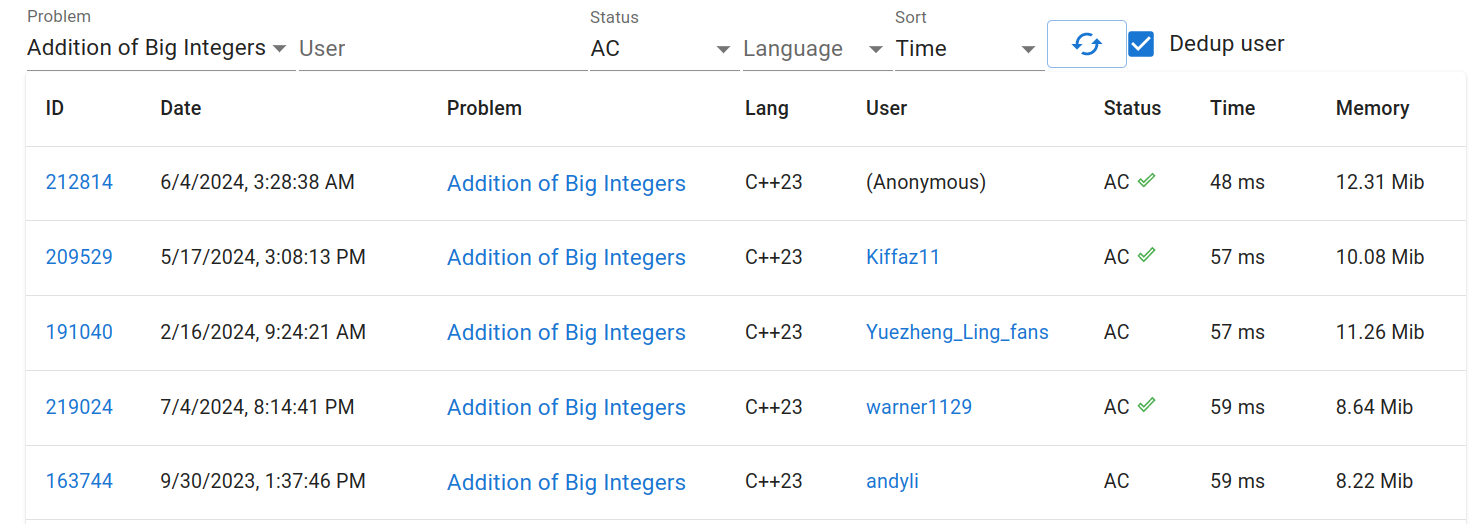

This submission on yosupo's Library Checker is currently the fastest implementation of big integers (as of July 27, 2024), outperforming other implementations without any complex optimizations (48ms vs. 57ms).

Multiplication

Well, I use the kid method, what do you expect? It got Time Limit Exceeded. The solution is to use FFT and/or Karatsuba. I was too lazy, and the problem statement said nothing about execution speed, so I settled down with the simplest trick.

Did I actually get the internship?

No(t yet).

I revealed that I would go to Singapore for an exchange semester in NUS. They were actually cool with that and told me I could go onboard after the semester ends.

One remark they made about me was that I "have good fundamentals, but lack in web development experience". I can't blame them. I can do webshit, I just chose to do other interesting projects.