- Preface

- nullptr/NULL/0

- Use before initialization/after free

- int a[n];

- Reinterpret-cast

- int* a, b, c;

- Size as a function parameter?

- Hungarian notation

- "Showing off"

- -> (The arrow operator)

- char* x = "Alice";

- printf("%c %c ", *++ppp, --*ppp);

- const int* p vs int* const p

- int pop(), exit code, and error handling

- Return value or Function argument?

("C++ Weekly with Jalsol Turner")

In this course, you'll be learning about pointers and manual memory management, which has always been a key feature of C/C++. It assumes you are capable of doing things (unfortunately, you probably aren't, and I'm not that much better either).

If you are from the "High Quality" program of HCMUS and your lecturer of CSC10002 happens to be Dr. Dinh Ba Tien, then you can read this as well (both courses are exactly the same, from the theory classes to the lab sessions).

If your lecturer happens to be someone else (or perhaps you don't take any CS class), you can still read this, but remember that this note is based on my experience with CS162.

I am open to all suggestions! If there is something you would like to add/correct (that is related to the course), please message/email me. Thank you so much!

Preface

I assume you have read my notes on CS161, and you know how I write my content.

Once again, if you see vulgar language from me on this blog, it's most likely

satirea safety warning and there's no intention to hurt anyone. Don't take it personally.

I will also assume that you know your lessons from the lectures. I will not be discussing basic concepts. This is more like an expansion to provide deeper knowledge. Thus, this blog can be useless for reviewing your lessons. For review, check out Study with 22APCS2.

>I have renamed it to "insight notes"

>and made a point that this note is not for lessons review

>and I'll assume that you study properly

nullptr/NULL/0

The null pointer is a special pointer. It points to the memory block with the address 0. Usually, this is used to tell that this pointer does not point to anything.

int* ptr;

ptr = nullptr; // Standard C++ (since C++11)

ptr = NULL; // Standard C/Old C++ (before C++11)

ptr = 0; // Exactly the same as ptr = NULL but it is not recommended

if (ptr == nullptr) {

// pointer does not point to anything

}

In fact, some functions return nullptr if they report a failure related to pointers. Usually, they are functions adopted from C (modern C++ functions throw exceptions instead).

#include <cstdio> // std::FILE, std::fopen

// the C way to open a file

std::FILE* fp = std::fopen("some_file", "w");

if (fp == nullptr) {

// can't open the file

}

NULL is an old thing from C. NULL is implementation-defined, which means that how it's defined depends on the compiler. From the C documentation, NULL may be:

- an integer

0 - a pointer

(void*) 0 nullptr(since C23, to comply with the use of the modern null pointer)

There are many reasons why

nullptrshould always be preferred. Our intention is clearer to the compiler.nullptrcan be converted to any pointer type but not integral types, which avoids ambiguity, compared toNULL.

void f(int) {

std::cout << "f(int)";

}

void f(void* /* accepts any pointer */) {

std::cout << "f(void*)";

}

int main() {

f(nullptr); // will call f(void*)

f(NULL); // NULL can also be implicitly cast to an int,

// it won't know whether to act as an int or a pointer,

// causing a compile error because of ambiguity

}

Use before initialization/after free

In the second CS162 lecture of the first week, I asked Dr. Tien a question with 2 scenarios. I am a little bit disappointed because he didn't provide us with a way to avoid bugs in those scenarios, which was my intention of asking in the first place.

Before initialization

int main() {

int* p; // no initialization

std::cout << *p << '\n';

}

This is dangerous.

A pointer is still a variable. Since there is no initialization, a random/garbage value is assigned. You don't know which part of the memory you are working with. It is the same as fucking without looking and you insert into the wrong hole.

Unless you have a reason to declare a pointer without pointing it to anything, you should not do it. You may assign

nullptrto it just in case.

After free

int main() {

int* p = new int;

// ... use p

delete p;

std::cout << *p << '\n'; // vulnerability

}

This is also dangerous. But a lot more dangerous. This is an actual vulnerability that got exploited in the past.

A lot of systems got fucked in the ass because of it. A whole lot of money went down the drain because some stupid and careless programmers forgot this could happen.

The object that p points to is now gone. However, p still points to that same block of memory where the object used to live, even after freeing.

If you are bloody lucky, nothing wrong will happen. If you are not (which is usually the case), some other objects may occupy the memory block that p points to. Thus, you will have illegal access to an object you are not supposed to control.

Hackers can somehow find a way to exploit that vulnerability. For example, if the "some other objects" are credential information (username, password, etc) or any other sensitive data, the hacker can retrieve/modify them via p (the invalid use-after-free pointer).

One of many possible fixes is to assign

nullptrto the pointer right afterdelete:

int main() {

int* p = new int;

// ... use p

delete p;

p = nullptr; // nullptr assignment right after delete

std::cout << *p << '\n'; // vulnerability

}

int a[n];

Explanation

Dr. Tien provided a scenario where we would like an array with dynamic size. Some may have tried this:

int main() {

int n;

std::cin >> n;

int a[n]; // declaration

}

Here's the catch: the above declaration only works for some compilers. If you use MSVC (which is used by Visual Studio), this won't work since n is not a constant. It is because the current C++ standard forbids such declaration.

The (textbook, not-really-good but allowed to use in CS162) C++ way to declare a dynamic array is by using new.

int main() {

int n;

std::cin >> n;

int* a = new int[n];

delete[] a; // DO NOT FORGET TO DEALLOCATE

}

Or, since RAII is introduced, we can have a lot of nice things in C++. The modern way is to use std::vector (but you are not allowed to use it for the course anyways, this is just an introduction).

#include <vector> // std::vector

int main() {

int n;

std::cin >> n;

std::vector<int> a(n);

// a will deallocate itself, no need for manual control

}

Also, with the benefit of RAII, we can replace the raw pointer with smart pointers, a (very cool) feature of C++. However, it is still a pointer (just a smarter one) and we don't have the benefits of an actual std::vector.

#include <memory> // std::unique_ptr, std::make_unique

int main() {

int n;

std::cin >> n;

std::unique_ptr<int[]> a = std::make_unique<int[]>(n);

// a will deallocate itself, no need for manual control

}

Or, if you feel adventurous/nostalgic/cool/dumb, you can even use the C way:

#include <cstdlib> // the C++ version of stdlib.h

// std::malloc

int main() {

int n;

std::cin >> n;

int* a = (int*) std::malloc(n * sizeof(*a));

std::free(a); // DO NOT FORGET TO DEALLOCATE

// std::free is used to free the allocation

// made by std::malloc, std::calloc...

}

You have to calculate manually how much memory you would like to allocate with std::malloc. For the keyword new, that value is calculated by the compiler.

History

Variable-length arrays (VLA) were introduced in C99. And boy was it a mistake. A lot of problems arose (you can read the StackOverflow thread below for more), so the C++ committee decided not to integrate that into C++.

Why aren't variable-length arrays part of the C++ standard?

Reinterpret-cast

Pointer disguise

Addresses are just numbers. The value that a pointer holds is just a number. What if a clueless you decide to assign an address of a pointer of type A, to a pointer of type B?

You have to be explicit to do the following in C++:

int* a;

float* b;

a = b; // NOT ALLOWED IN C++

// (allowed in C but will raise a warning)

a = (int*) b; // OK

It is a mechanism to protect you from accidental a = b. If you want to do so, you have to explicitly do the cast: a = (int*) b.

This is what the cast does: we disguise

bas anint*, so(int*) blooks like it's anint*, pointing to anintvariable (while it's pointing to afloat, real sussy wussy ඞ*)*.

Then, we can do the assignmenta = (int*) bbecause both sides have the type ofint*.

This kind of cast is called the reinterpret cast.

In C++, there exists a keyword called

static_cast. C-style cast is used to simplify writing in this blog and is not recommended in almost all cases.

Or maybe think twice before doing any sort of cast.

// C++-style cast

int a = static_cast<int>(b);

int* pa = static_cast<int*>(pb);

// C-style cast

int a = (int) b;

int* pa = (int*) pb;

Dereferencing the disguised pointer

This bears another question: what is the value of *a?

int* a;

float* b;

b = new float{5}; // *b == 5

a = (int*) b;

std::cout << *a << '\n'; // is *a == 5?

We let *b = 5 and do the cast. The value of *a, however, is not 5. Assuming both int and float have 4 bytes (which is correct for most modern systems nowadays), the output for the above code is 1084227584. This appears to be a random value, but it is not.

Fundamentally,

floatandinthave different mechanisms to represent numbers. With the same bit representation, the value of afloatis different than that of anint(that's all you need to know for now, I won't go into the details).

The bit value of 5 as a float is 01000000 10100000 00000000 00000000. The bit value of1084227584 as an int is, well, also 01000000 10100000 00000000 00000000.

Now you see the effect of this cast, and why it is called "reinterpret-cast". It takes the bit value of one type and uses it to represent the value of another. Due to the difference in how

floatandintrepresent a number, with the same bit value, we get (totally) different numbers.

What else?

There are many things I would like to talk about.

- The real terminology for "pointer disguise", as mentioned in the comment, is "type punning". But what the fuck is this wording anyways?

- The example we have been using so far,

floatandint, have the same size (the same number of bytes). To explain what happens if we uselong longandintinstead, I would have to teach stuff like endians (which will be covered on CS201).

The use of reinterpret-cast is quite rare. It is considered a tricky hack. Do not use it if you aren't sure what you are doing.

One famous example is the Fast Inverse Square Root, implemented in Quake III. They needed to manipulate the bit representation of a float value, but it was (and still is) forbidden in C/C++, so they reinterpret-cast to an int.

There are safer ways to reinterpret-cast without using pointers.

// The better C way

union u_fi {

float f;

int i;

};

u_fi u;

u.f = 5;

std::cout << u.i << '\n'; // prints 1084227584

// standard C++ (since C++20)

#include <bit> // std::bit_cast

float f = 5;

int i = std::bit_cast<int>(f);

std::cout << i << '\n'; // prints 1084227584

Fast Inverse Square Root — A Quake III Algorithm

int* a, b, c;

What the fuck?

This is one of the things that may confuse new people.

int* a, b, c;

With the declaration above, only a is a pointer. b and c are normal variables. Yes.

If you would like to declare all of them as pointers, do the following:

int *a, *b, *c;

Coding convention for pointer annotation

There have been many debates on different ways to annotate things. The pointer annotation is no exception.

Many people let the * be next to the type (int* a) because it can be understood that int* is a type. However, this kind of declaration leads to our aforementioned problem.

int *a would solve that problem, but it would be difficult to, say, find all pointers of int in a file using a search tool.

It depends on you to choose what style to follow. I personally stick to the int* a one and avoid declaring multiple pointers on the same line. If I want many pointers, they will have to be declared on different lines. This is recommended when you program in C++.

Stick to one pointer per declaration and always initialize variables and the source of confusion disappears.

- Bjarne Stroustrup (the creator of C++)

int* a;

int* b;

int* c;

Another way to deal with this is to define a new type with aliasing. For modern C++, that can be done with the keyword using (and is the recommended way). For C and older C++ versions (before C++11), typedef has to be used.

using int_ptr = int*; // The * sticks to the type

int_ptr a, b; // both a and b are pointers of int

Or, use C++'s smart pointers (although they were born to solve a completely unrelated problem):

#include <memory> // std::unique_ptr, std::shared_ptr, std::weak_ptr

std::unique_ptr<int> a, b;

Why?

Disclaimer: I am not a C/C++ historian.

From what I have researched, it is history.

The * is the dereference operator at heart, and in C, it should be tied to the declarator since C emphasizes syntax.

My speculation: To enable backward compatibility, C++ compilers have to be able to compile that as well. I suppose that is the problem that Dr. Tien talked about shortly after the first lecture of the second week of 22APCS2.

C++, however, emphasizes types. It focuses a lot more on types. That is why the * follows the type. Read Bjarne Stroustrup's opinion on this matter.

Obviously, there are a lot more reasons why C compilers decided to do that. But I'm not old and knowledgeable enough to talk about it.

Stroustrup: C++ Style and Technique FAQ

Size as a function parameter?

Dr. Tien was "wrong"

Dr. Tien mentioned that to avoid the mismatch between the actual size of a string and the independent value, an independent value for a C-string size is not needed.

However, in practice, it's the exact opposite. This is one of the most well-known vulnerabilities ever existed: buffer overflow.

Here are some examples:printf and scanf are two popular functions used for reading and writing in C. They do not require a size, and they are vulnerable to the aforementioned attack.

By passing a size, you are in control of how much of your data is being processed. Without a size, you may have to process data that your buffer cannot control, leading to the illegal access of other memory blocks. You cannot simply check if something is out-of-bound. Hackers can exploit this to modify data illegally.

As an example, since C11, scanf_s is introduced. It requires a parameter that indicates the size of the output. The _s suffix stands for "safe". It's not random that a "safe" version of a function requires a size value.

Strings can get you hacked! (buffer overflows, strcpy, and gets)

Or, was he?

Also in the small discussion after the first lecture of the second week of 22APCS2, I mentioned this problem. He was (unsurprisingly) aware of that vulnerability. However, his intention was that it would be redundant if we move to std::string.

At some point, we will not use C-string anymore and move on to the glorified

std::string, the recommended way to use strings in C++.

It is a struct() that wraps around a dynamically allocatedchar*and some other variables (like the size variable). It also comes with helper functions that make life a lot easier and safer.

(**): It is actually a class. However, specifically in C++, there is no major difference between a struct and a class.

Because std::string has an internal member that stores the size, you do not need another one. If you need to get the size, just get its value (via the size() function). There is no need to recalculate the length of the string by calling strlen every time, like with the C-string. Recalculation will only take place when the string updates its content.

void print_size(const std::string& s /* no need for a separated size variable */) {

std::cout << s.size() << '\n'; // pulls out the size variable,

// no recalculation

}

std::string s = "Hi."; // guaranteed to be null-terminated

print_size(s); // prints 3

(Please note that you are not allowed to use std::string on this course)

Hungarian notation

Dr. Tien named the variable that points to the head of the linked list pHead.

The way of naming variables like this is called the Hungarian notation.

int iSize; // int size

std::string strName; // string name

char* pchArr; // pointer char array

float fU; // float u

Basically, they shorten the name of the type and make that the prefix of the variable name.

This naming convention is ancient. **Back in the day, they didn't have advanced IDEs. C++ had, and still has, implicit conversion (which is bullshit, see the last example in the nullptr/NULL/0 section), so it is used to show whether implicit conversion could happen.

int iSize;

float fU;

iSize = fU; // this compiles normally but causes the loss of data

// (the digits after the decimal points)

// noticing that i != f, the programmer can see implicit conversion

However, modern tools make this completely unnecessary. You can see the type of the variables just by hovering over them with modern IDEs, and the compiler does warn you about the loss of data by implicit conversion with the right configuration, like the flag -Wconversion.

If you change the type of fU to int, you will have to rename fU to iU in every single file that contains it. This may take a lot of time, and even with modern tools (Find-and-Replace, variable rename using LSP, etc), it still requires some effort.

For weakly typed languages (like Python and JS), this notation can still be useful, but I don't see anyone using it, to be honest.

My opinion on naming conventions can be found in my CS161 notes (specifically the "Variable naming" and the "Coding styles" section).

You can read Bjarne Stroustrup's opinion on the Hungarian notation as well.

"Showing off"

Note: Some concepts go way beyond the scope of the course.

TL;DR: Guy tried to show off, then ended up showing off his problems.

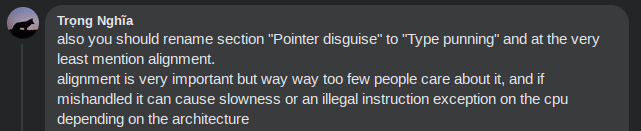

The image above was taken from the class CLC06, during their CSC10002 lecture.

The task was to fix a memory leak. A student (you probably know who) offered to do it. He added irrelevant stuff that did not help solve the problem. He managed to fix it anyways, but this exposed something I would like to talk about.

Constructor

Note: You are not taught to use constructors in this course. You will learn more about this in CS202.

The constructor is a function that runs when an object is created.

struct Node {

Node() {

std::cout << "Created!" << std::endl;

}

};

int main() {

Node a; // Creates a new variable of type Node,

// so this will call Node()

// -> prints "Created!" and ends the line

}

Usually, people use structs to gather various data into one type. They only hold data and don't represent object models, which is why you should never write functions inside them. Constructors are somewhat allowed, but their uses are very limited as well.

data = 0xdeafbeaf;

0xDEADBEEFis a special magic value used for debugging, something to indicate an error that should not happen at all. It was used to crash the whole system if addressed.

From my personal experience, this value is rarely used nowadays.

- This is ✨m i s s p e l l e d✨

- It's actually

0xDEADBEEF(spelled "dead beef", not "deaf beaf").

- It's actually

- It is misused

- By definition, it is only used to denote whether a behavior should not happen.

- I do not see why the default value for the data of a valid node should be assigned a value that represents an error.

- I do not see why calling the constructor should be treated as an error.

- If you do not want the constructor to be called, don't define it in the first place. You may consider disabling constructors altogether (I won't explain how to do this, wait until CS202 or do the research yourself).

By showing off trying to avoid "safety issues", he showed off his issues of not understanding what he programmed.

Assignment in constructors???

From the C++ Core Guidelines, initialization should be used to initialize (ofc). Assignment may not represent the clear intention and may introduce a "Use before set" bug.

So, instead of

Node() {

data = 0;

next = nullptr;

}

do this instead

Node() : data{}, next{} {}

// Note that I don't write `data{0}`, because I might change the type of `data`

// to something else (e.g. std::string)

// If I let data be an int, data{} will assign 0 to `data`

// If I replace `int` with std::string, then `data{0}` will fail,

// but `data{}` will initialize an empty string

Or, in this specific case, also from the C++ Core Guidelines, prefer in-class initializers to member initializers in constructors for constant initializers.

struct Node {

int data{};

Node* next{};

// No need to implement Node()

};

You may read the guidelines for more information. It's short and straight to the point.

Conclusion

The code is not the most important part. Notice that I told you this code did not help to solve the original problem at all.

Don't try to show off if you have no clue what you are doing.

-

Other interesting comments you'd probably like to see on the same guy

-> (The arrow operator)

What is it?

Suppose the following code:

struct Node {

int data;

Node* next;

};

int main() {

Node* ptr = new Node{5, nullptr};

std::cout << *(ptr).data << '\n'; // prints 5

std::cout << ptr->data << '\n'; // prints 5

}

As you can see, *(ptr).data and ptr->data are equivalent. ptr->data is much cleaner and you can think of its meaning as "ptr points to the member data of the element".

This turns

*(*(*(*(ptr).next).next).next).next

into

ptr->next->next->next->next

The white spaces around it

Man, you don't know how cringe I felt when they did

cur -> next

Please. Do not do that. That is ugly. That screams unprofessionalism.

I was surprised to see people who I thought knew how to code do this (maybe they do code very well in other languages, but not C or C++).

The ., :: and -> have one thing in common: they are used to access something. It makes perfect sense that they also follow the same convention.

You don't do

A . B

or

A :: B

so please, don't do

A -> B

Make it right, don't add those spaces:

A->B

char* x = "Alice";

Question

This came from a lab question that caught me off-guard.

The question is: what will be the output of the program?

// main.c

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

int main() {

int i, n;

char* x = "Alice";

n = strlen(x);

*x = x[n];

for (i = 0; i <= n; ++i) {

printf("%s ", x);

++x;

}

printf("\n", x);

}

- A. Alice

- B. ecilA

- C. Alice lice ice ce e

- D. lice ice ce e

The unexpected answer

The answer is that this program will crash, without printing anything.

The line that causes the crash is *x = x[n];. It is because "Alice" is actually a constant string.

Analysis

Note: I advise reading the TL;DR only if you don't want to read the overcomplicated analysis.

TL; DR:

In C++, the string literal (double-quoted string) isconst char[N]. The pointer now points to a constant string, so you can't modify it.

In C, the string literal ischar[N]. However, I was fooled. I found out the hard way that although it's achar[N]and notconst char[N], in this specific case, it belongs to the read-only data section of the program, which means it's also constant. It is specified in this C FAQ.

Program crash

At first, I assumed it would run normally. However, this program will cause a runtime error (it crashes). And it will print nothing.

The compiler I used was gcc-11, on an x86-64 Linux system.

The first thing I did was check for any illegal memory manipulation. By compiling with the flag -fsanitize=address, the address sanitizer returned this message:

AddressSanitizer:DEADLYSIGNAL

=================================================================

==36679==ERROR: AddressSanitizer: SEGV on unknown address 0x562da3a88020 (pc 0x562da3a872cd bp 0x7ffca6f863e0 sp 0x7ffca6f863d0 T0)

==36679==The signal is caused by a WRITE memory access.

#0 0x562da3a872cd in main (/tmp/main+0x12cd)

#1 0x7f715227cd8f in __libc_start_call_main ../sysdeps/nptl/libc_start_call_main.h:58

#2 0x7f715227ce3f in __libc_start_main_impl ../csu/libc-start.c:392

#3 0x562da3a87164 in _start (/tmp/main+0x1164)

AddressSanitizer can not provide additional info.

SUMMARY: AddressSanitizer: SEGV (/tmp/main+0x12cd) in main

==36679==ABORTING

After some debugging, it can be seen that the assignment *x = x[n] is the reason for the crash. More precisely, changing the value of *x crashed the program (hence The signal is caused by a WRITE memory access).

It was weird. I thought I should've been able to modify the string that way since string literals in C are not constant. Immediately, I suspected that the string was, however, constant.

I went to check inside the .rodata section, which is for read-only data. By disassembling the program with objdump -d -j .rodata main, this is the following output:

main: file format elf64-x86-64

Disassembly of section .rodata:

0000000000002000 <_IO_stdin_used>:

2000: 01 00 02 00 41 6c 69 63 65 00 25 73 20 00 0a 00 ....Alice.%s ...

The first 4 bytes, 01 00 02 00, are irrelevant to our problem. They represent the value of _IO_stdin_used. This is explained in this thread and you can read more if interested (note: user202729 a.k.a. Bui Hong Duc appeared in that thread 😮).

Then, here comes the strings that appear in the program:

41 6c 69 63 65 00is the hexadecimal representation of"Alice".25 73 20 00is the hexadecimal representation of"%s ".0a 00is the hexadecimal representation of"\n".- Note that each of them contains an extra byte

00. That is the terminating null character'\0'.

From that, it can be concluded that "Alice" is constant, because of its appearance in the .rodata section.

After some more research to find what the C standard has got to say about such behavior, I found this C FAQ. Yes, I went all the way to disassemble the program, while this behavior is well documented.

To be more precise: x is not the string itself, it's just a pointer that happens to point to a constant string.

To modify the content of the string, replace:

char* x = "Alice";

with:

char str[] = "Alice";

char* x = str;

What this does is that it copies the content of "Alice" (the constant string) to another mutable string (which is str in this case). Now, you can modify str directly or via x.

Note: As for C++, it is explicitly stated that a string literal of size N has the type of const char[N].

The result after fixing the crash

Let's assume that the replacement mentioned is applied.

Then, *x = x[n] is basically assigning x[0] to '\0'. The string is "\0lice\0".

printf will print every character in the string until it encounters a '\0'.

- In the

for-loop:- In the first iteration, it will print nothing.

- In the next 4 iterations, it will print

lice, thenice, thence, thene. - In the last iteration, it will print nothing.

- In the final

printfstatement,"\n"does not have any format specifiers, hence it will just print a new line andxdoesn't affect anything.

→ The final output is lice ice ce e .

printf("%c %c ", *++ppp, --*ppp);

Also from a lab question, which I found interesting. I was not fooled this time.

Question

What will be the output of the following program?

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

char a[] = { 'A', 'B', 'C', 'D' };

char* ppp = &a[0];

*ppp++; // Line 1

printf("%c %c ", *++ppp, --*ppp); // Line 2

}

- A.

C B - B.

B A - C.

B C - D.

C A

Analysis

Line 1 increases the pointer to the next address.

It is effectively the same as:

*ppp; // Dereference, but the value after that is unused so no effect at all

ppp++; // Pointer increment

Line 2 causes undefined behavior.

From the C documentation:

Order of evaluation of the operands of any C operator, including the order of evaluation of function arguments in a function-call expression, and the order of evaluation of the subexpressions within any expression is unspecified (except where noted below). The compiler will evaluate them in any order, and may choose another order when the same expression is evaluated again.

There is no concept of left-to-right or right-to-left evaluation in C, which is not to be confused with left-to-right and right-to-left associativity of operators: the expressionf1() + f2() + f3()is parsed as(f1() + f2()) + f3()due to left-to-right associativity of operator+, but the function call tof3may be evaluated first, last, or betweenf1()orf2()at run time.

This means that for the code in the question, there is no way to determine whether *++ppp or --*ppp will be executed first. This is implementation-defined, and the result may vary between different compilers.

- If

*++pppis executed first, then the output isC B - If

--*pppis executed first, then the output isC A

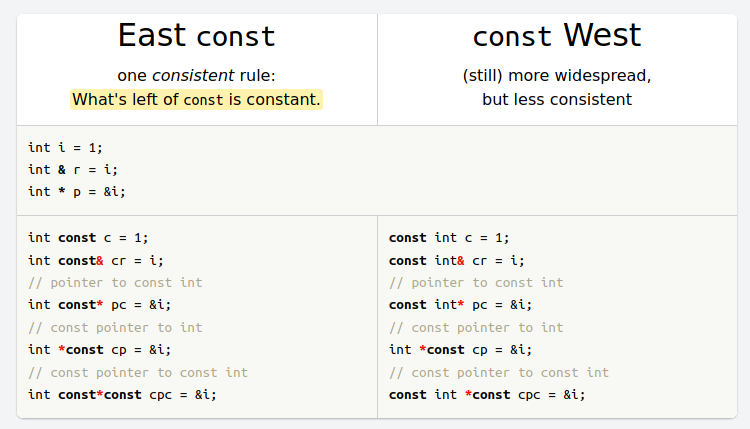

const int* p vs int* const p

This is another case of confusing notations.

East-const vs West-const

const int a is the same as int const a. There are terms to distinguish them, and there are even debates about them.

const int ais west-const (or, some people call it const-west)int const ais east-const

West-const is more popular, due to the fact that it's human-friendly. Many people use it, I use it, too. However, human languages are fucked. They are inconsistent.

East-const is slowly getting more recognition, because it is more stable (which I will talk about in the next part).

Understanding east-const vs west-const is very important. However, I am not seeing west-const being replaced anytime soon, so I still use it.

What's so cool about east-const?

From https://hackingcpp.com/cpp/design/east_vs_west_const.html

You can see the rule: What's left of const is constant.

What does that mean?

Suppose we have int const* const p. Let's try to read it from right to left.

... pis a variablep... const pis a variablep, which is a const... * const pis a variablep, which is a const pointer... const* const pis a variablep, which is a const pointer, which points to a constint const* const pis a variablep, which is a const pointer, which points to a const int

You don't get such consistency with west-const, which causes the confusion in the first place.

Debunk the brain fucker

The following will be very easy once you get the idea of east-const and west-const.

If you try to read from right to left, just like what we have just done:

const int* pis a normal pointer that points to a constant intint* const pis a constant pointer that points to a normal int

You can also think of it this way (ofc they are not valid C/C++):

const int* p⇒(const int)* pint* const p⇒(int)* const p

They are quite different:

| const int* p | int* const p |

|---|---|

| You can point to both const int and int | You can only point to int |

| You can change the value of p (e.g. you can point to const int a with p = &a, then point to int b with p = &b afterwards) | You can't change the value of p (e.g. if you declare int* const p = &x then you can't do p = &y afterwards) |

It's easy to mess things up. If you want to switch from east-const to west-const or vice versa, here is how you do it:

-

const int* pis west-const. The east-const version isint const* p. -

int* const pis east const. There is no direct west-const version. You may use type aliasing like this:using int_ptr = int*; const int_ptr p; // const (int*) p // west-const again

int pop(), exit code, and error handling

he do a little trolling

Dr. Tien threw all of us off guard with the prototype int pop(Node*& stack). A student returned the value at the top of the stack. If there is nothing inside the stack, then he would return -1 to report an error.

However, since the stack can contain any value it wants within the range of an int (including -1), this is not a nice way to handle error. What if the value of the stack top is -1? That is not an error, isn't it?

Dr. Tien actually wanted to return a bool. 1/true if it can be popped, 0/false otherwise.

To get the value of the top then pop it, you should split the task into a procedure of steps:

- is it empty?

- Get the top

- Pop the top

Why int? Why int main()?

If our function only returns true or false, then bool should be enough to do the job, and not cause any unnecessary confusion.

In many cases, there are a lot more things to report, more than just either something is done successfully or not. This requires more than 2 values, and bool is simply not enough.

The term for this value is called "exit code" or "status code".

Which value is used to represent which status, is defined by the programmers. There is usually no universal set of rules for that. Each company/organization has their own rules. However, there are some conventions that (almost) everyone uses:

- For desktop applications,

0means the program exited successfully,1means the program exited failed,255(or-1) means out-of-bound error, etc. - For web applications, they follow this convention of HTTP response status codes.

This explains a lot of things.

- Your program has to return an exit code, which is why

main()has to be anintfunction, and not avoidfunction by any means. - You often see

return 0;at the end ofint main(). This means that the program exited successfully. Nowadays, if you don't write that at the end, the compiler will do that job for you*. 404is an HTTP response status code. It does indeed meanNot found, as you all know.

(): int main() is the only function that's implied to return 0 if there is no return statement. Other functions that are not void have to return something.*

Exceptions

You will learn this in CS202. This is merely an introduction.

Another way to handle errors is to throw exceptions. To check whether an exception is thrown, try-catch is used.

This is kind of nice that you can keep the returning type of the function to be void, which may represent the intention of the function clearer. You also don't need to come up with a list of obscure numbers.

However, some consider the excessive use of try-catch to be a bad thing.

Return value or Function argument?

Dr. Tien wanted to get the value of the top and pop it at the same time. He suggested 2 prototypes:

// Return value

Node* pop(Node*& stack) {

// returns a pointer to top

}

int main() {

// ...

Node* top = pop(stack);

if (top == nullptr) {

// empty stack

}

// ...

}

// Function argument

int pop(Node*& stack, Node*& out) {

// modifies out, returns exit code

}

int main() {

// ...

Node* top;

int code = pop(stack, top);

if (code == 0) {

// empty stack

}

// ...

}

There are advantages and disadvantages to both, but they are usually historical and very specific to certain cases.

Why function argument?

- It allows the return of exit code.

- You couldn't return the value of a big object back then, only things like

ints and pointers.- If it could return a big object, it could cause a copy anyways.

- You can pass a stack-allocated variables (C++'s references do this under the hood):

void f(char* buffer, int size);

int main() {

// allocated on the stack

char buffer[512];

f(buffer, 512);

// no need to delete

}

char* f(int size);

int main() {

// allocated on the heap

// no explicit `new` keyword

char* buffer = f(512);

// no `new` but have to `delete`

delete buffer;

}

Why return value?

This method is the modern C++ way to return multiple values.

- Instead of exit code, exceptions can be used.

- Modern compilers can perform optimizations to avoid copy operations (e.g. copy elision).

- Fewer parameters, in case there are so many things to return.

- Avoid ambiguity in certain cases.

struct number_ranges {

int min, max;

};

number_ranges f() {

// ...

return {min, max};

}

int main() {

// C++17 structured binding

auto [min, max] = f();

}

void f(int& out_min, int& out_max) {

// ...

out_min = min;

out_max = max;

}

int main() {

int min, max;

f(min, max);

}